Tyger, tyger, burning bright

In the forests of the night,

What immortal hand or eye

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?

- William Blake, The Tyger

Plants and animals don't have image rights (correct me if you must). The immortal hand or eye doesn't claim copyright on creation, and evolution would make that area of law very murky anyway, so the entrepreneurial designer Rob Law re-framed the tiger for his Trunki children's ride-on suitcase:

Then his business rivals had a go with their not dissimilar Kiddee Case:

It's not just the tygers which are in contention today. To depict the relentless colours of the fauna in court I've brought wax crayons. And I'm guessing a bit. From my restricted-view seat I can spot a flash of orange in front of the bench but not enough to see whether it's a Trunki or a Kiddee Case.

It's not just the tygers which are in contention today. To depict the relentless colours of the fauna in court I've brought wax crayons. And I'm guessing a bit. From my restricted-view seat I can spot a flash of orange in front of the bench but not enough to see whether it's a Trunki or a Kiddee Case. Just one issue is being examined in PMS International Limited v Magmatic Limited: what is the significance - in design infringement terms - of the fact that there is no surface decoration on Trunki's Community registered design? I hope counsel will be very clear in their arguments: overlooking the scene is a portrait of John Fielding, the blind magistrate.

The unsung hero is ye olde measured drawing, by hand. A key question today is whether proper line drawings - rather than a 3D-effect monochrome computer-aided design - would have clarified what the Trunki image rights were supposed to protect. Above is Magmatic Limited Registered Design no. 000043427-0001.

The other day I was watching a short film of a dinosaur skeleton being excavated. Cameras were there, yes, and paleontologists brushing sand from vertebrae - but also a patient artist making an essential record of what the camera can't see.

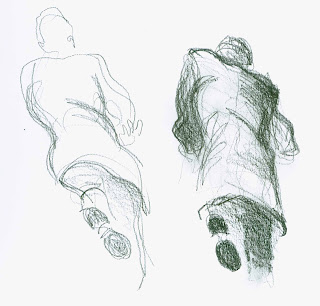

Meanwhile I'm wasting time drawing a Friesian cow when I notice that counsel has his knee on the table. Alternate knees but mainly the left. In full flow he switches rapidly from one knee to the other. Without falling over. His spine and suit are under enormous strain.

Later on I try this at home. Don't. Fronting up to the Supreme Court bench can define careers and must always generate a huge slug of adrenalin, but even so this is the most interesting forensic fight-or-flight posture I have ever seen.

Come the evening I'm on my way to an event when, in an inadvertently Faustian way, I conjure up Lord Neuberger on the wet pavement. He's had a busy day facing garish plastic followed by a London commute and won't want to be accosted by a random fan.

I get to the event, a fundraising talk for portersprogressuk.org by ace mountaineer Stephen Venables. Luke Hughes is there. I accost him. He'll know how high the Supreme Court barristers' benches are. He designed them, and my kitchen table. 74cm is the answer.

I get to the event, a fundraising talk for portersprogressuk.org by ace mountaineer Stephen Venables. Luke Hughes is there. I accost him. He'll know how high the Supreme Court barristers' benches are. He designed them, and my kitchen table. 74cm is the answer.He is also a gifted mountaineer and has climbed the north face of the Eiger with Venables while discussing Mozart and Proust as they do. Heights hold no fears for Hughes. He talks of overcoming the Ministry of Justice's health-and-safety fears about installing ladders in the Supreme Court library.

I've met him before, when he was giving a talk in the Supreme Court. On that occasion he asked me if I was a climber. I can't even rest my knee on my desk.

I've met him before, when he was giving a talk in the Supreme Court. On that occasion he asked me if I was a climber. I can't even rest my knee on my desk.Update: on seeing this post a friend wrote: 'I did jury service earlier this year. The mangled postures of the barristers were the most fascinating thing about it.'

@otium_Catulle

Category